Cultura durant el col·lapse / Culture During Collapse

(first published in ARTIGA magazine issue 40 2023)

(cat)

“La diferència entre un col·lapse millor o pitjor vindria determinada, al meu parer, pel fet que es materialitzi o no un genocidi.” — Jorge Riechmann

El col·lapse eco-social ja és aquí i és inevitable. Ja no es tracta de mitigar el col·lapse, sinó de com col·lapsar millor. Estem parlant d’un col·lapse amb causes multifactorials, com la crisi climàtica, l’escassetat d’aigua, de petroli i de minerals, amb totes les conseqüències que això comporta: guerres, migracions massives i inestabilitat política.

La idea d’una transició cap a una societat igual que l’actual però electrificada no és realista. Les dades científiques mostren que no tenim la quantitat suficient de minerals per poder subministrar tot el planeta amb energia elèctrica renovable. Per tant, ja és hora de deixar de banda la utopia tecno-capitalista i focalitzar els esforços en fer un canvi radical de societat.

Aquest canvi implica potenciar sistemes socials que ens ajudin a habitar millor el futur que ens espera. Segons Pablo Servigne, la solució és seguir el que ja molts fem: crear xarxes de suport solidari i d’acció social. Una idea oposada a la distopia individualista americana de sèries com Walking Dead, on es proposa la creació de búnquers autosuficients i militaritzats. Ara, més que mai, necessitem potenciar una societat solidària, feminista i ecosocial.

Quin paper té la cultura en aquest procés? L’investigador i arquitecte Albert Cuchí va realitzar un estudi sobre l’impacte ambiental de l’Escola d’Arquitectura del Vallès. Després d’analitzar tots els aspectes més tècnics (climatització, il·luminació, transport, etc.), va arribar a la conclusió que era en l’aspecte humà on realment es podia fer un canvi significatiu. Canviar el currículum de la facultat tindria molt més impacte que qualsevol modificació tecnològica. Va veure que, si tots els futurs arquitectes que sortissin de l’escola implantessin una arquitectura sostenible, l’escola realment contribuiria a una transició ecològica.

En l’àmbit de la cultura, podem aplicar una idea similar. El canvi significatiu el trobarem canviant el “software” i no el “hardware” de les institucions culturals. Per això, cal continuar potenciant una cultura inspirada en idees ecologistes i solidàries, aportant visions i imaginaris col·lectius de models alternatius de pensar i d’organitzar-se. Només des d’aquesta posició evitarem posar fi a tota la vida al planeta.

Cal subratllar que és necessari centrar-nos no només en el contingut, sinó també en les formes de transmetre la cultura. La cultura segueix estant, en molts àmbits, focalitzada en el model de consum i d’entreteniment. Són encara massa poques les organitzacions que proposen maneres de produir i compartir cultura basades en els processos i el diàleg amb l’entorn social. És decebedor veure, per exemple, que la competitivitat entre ofertes culturals encara és l’habitual. Competir entre pobles, festivals i museus per atraure més públic és completament innecessari si volem tenir un paper actiu en la supervivència al col·lapse eco-social.

Per a una transició eco-social, també hem de potenciar més que mai el treball emocional i les cures. Necessitem processos i connexions a llarg termini que acompanyin i dialoguin directament amb tots els altres àmbits de les nostres vides. Processos en els quals es gaudeixi de la cultura, que donin sentit i aportin visions complexes i reals a les dificultats socials, emocionals, econòmiques i ecològiques. I la responsabilitat d’això recau en les estructures des d’on produïm i consumim la cultura, no en l’artista individual.

Necessitem idees creatives i radicals per abordar els canvis que ens esperen. Malauradament, sembla que només així podrem evitar un ecocidi i genocidi planetari.

- Jorge Riechmann. Otro fin del mundo es posible, decían los compañeros, Mra Ediciones, Barcelona 2019.

- Alicia Valero. “Límites a la disponibilidad de minerales”, El Ecologista 83, Madrid 2014.

- Informe MIES, Una aproximació a l’impacte ambiental de l’Escola d’Arquitectura del Vallès: bases per a una política ambiental a l’ETSAV, 1999, Albert Cuchí i Burgos, Isaac López-Redondo.

(engl)

“The difference between a better or worse collapse, in my view, would be determined by whether or not a genocide occurs.” — Jorge Riechmann.

The eco-social collapse is already here and is inevitable. It is no longer about mitigating the collapse, but about how to collapse better. This collapse is caused by multiple factors, such as the climate crisis, water scarcity, and the depletion of oil and minerals, all of which lead to consequences like wars, mass migrations, and political instability.

The idea of transitioning to a society similar to the current one but electrified is unrealistic. Scientific data shows that we do not have enough minerals to supply the entire planet with renewable electric energy. Therefore, it’s time to abandon the techno-capitalist utopia and focus on making a radical societal change. This change involves strengthening social systems that will help us navigate the future that awaits us. According to Pablo Sevrigne, the solution lies in what many of us are already doing: creating networks of solidarity and social action, a stark contrast to the individualistic American dystopia depicted in series like “The Walking Dead,” which envisions self-sufficient, militarized bunkers.

Now, more than ever, we need to foster a society that is supportive, feminist, and eco-social.

What role does culture play in this process? Researcher and architect Albert Cuchí conducted a study on the environmental impact of the School of Architecture in Vallès. After analyzing all the technical aspects (climate control, lighting, transportation, etc.), he concluded that the most significant change could be made in the human aspect. Changing the faculty’s curriculum would have a much greater impact than any technological modification. He found that if all future architects graduating from the school implemented sustainable architecture, the institution would significantly contribute to an ecological transition.

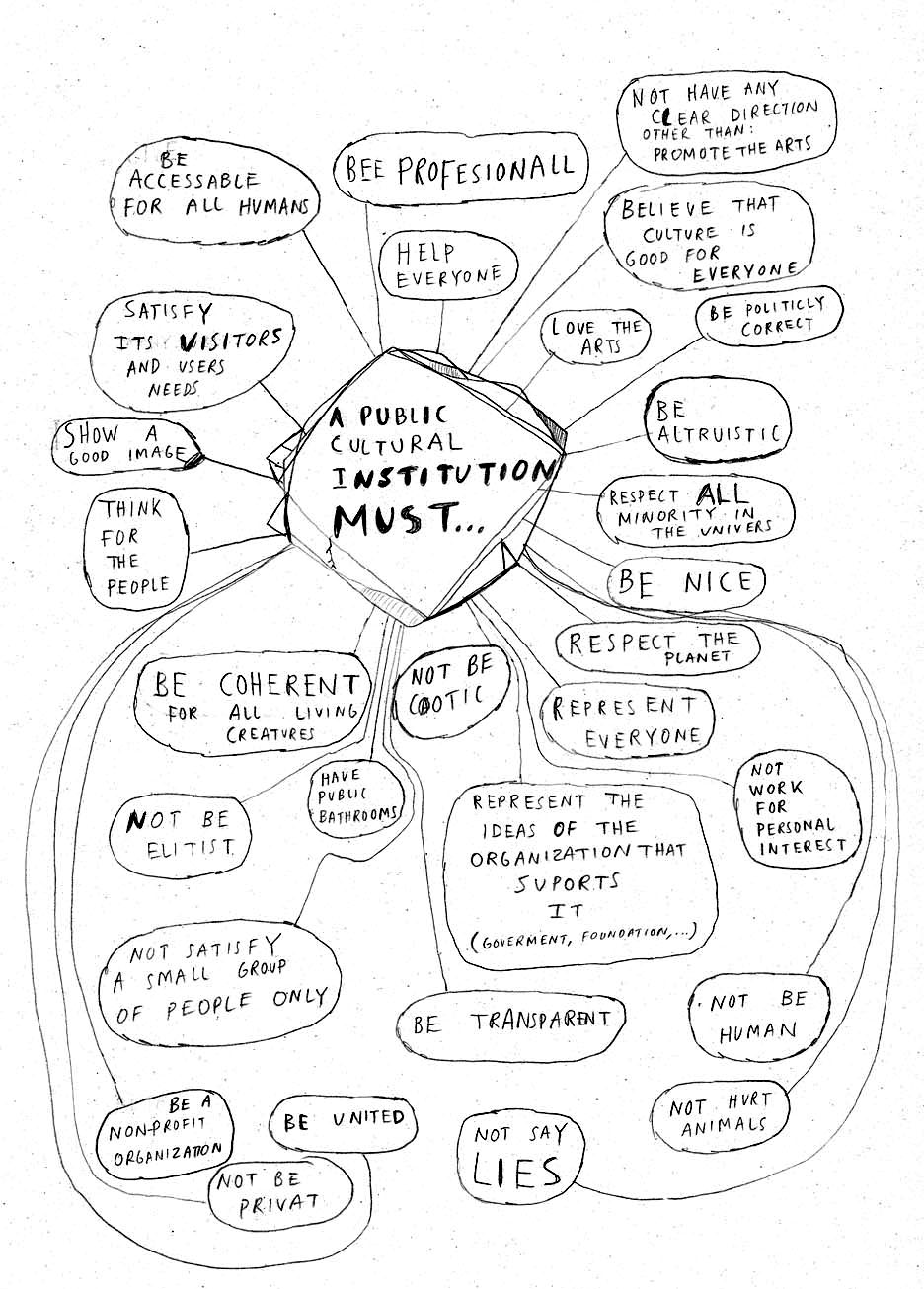

In the realm of culture, we can apply a similar idea. The significant change will come from altering the “software” rather than the “hardware” of cultural institutions. This requires us to continue promoting a culture inspired by ecological and solidarity-based ideas, providing collective visions and alternative models for thinking and organizing. Only from this position can we avoid the end of all life on the planet.

It is crucial to focus not only on content but also on the ways we transmit culture. Culture still largely revolves around consumption and entertainment. Too few organizations propose ways to produce and share culture based on processes and dialogue with their social environment. It is disappointing, for example, to see that competitiveness among cultural offerings is still the norm. Competing among towns, festivals, and museums to attract more audiences is entirely unnecessary if we aim to play an active role in surviving the eco-social collapse.

For an eco-social transition, we must also prioritize emotional work and care more than ever. We need long-term processes and connections that accompany and engage directly with all other areas of our lives. These processes should allow us to enjoy culture in ways that make sense and provide complex, real visions of social, emotional, economic, and ecological challenges. The responsibility for this lies with the structures from which we produce and consume culture, not with the individual artist.

We need creative and radical ideas to address the changes that lie ahead. Unfortunately, it seems that only by doing so can we avoid planetary ecocide and genocide.

- Jorge Riechmann, “Otro fin del mundo es posible, decían los compañeros,” Mra Ediciones, Barcelona, 2019.

- Alicia Valero, “Límites a la disponibilidad de minerales,” El Ecologista 83, Madrid, 2014.

- Albert Cuchí and Isaac López-Redondo, “Informe MIES, Una aproximació a l’impacte ambiental de l’Escola d’Arquitectura del Vallès: bases per a una política ambiental a l’ETSAV,” 1999.

////////////////////////////////

Entrevista amb el comissari Oriol Fontdevila per la Bienal d’Art de Tarragona 2023 sobre el projecte “Recerca sobre Taules” / Interview with curator Oriol Fontdevila for the Tarragona Art Bienale 2023 on Research about tables

(cat)

- Un aspecte que m’interessaria discutir de la teva investigació sobre la taula és l’efecte que busques aconseguir quan aquesta obra s’exposa en un museu. D’una banda, amb la taula, destaques un aspecte del display del museu que sovint passa desapercebut. Però, alhora, quan redueixes tota la sofisticació del disseny del display al component de la taula i en subratlles la seva condició de mínim comú múltiple, sembla que també aspiris a revelar el museu com un artefacte molt més domèstic i quotidià del que aparenta inicialment.

Exacte, parlar de la senzillesa o quotidianitat de la taula és una manera de parlar de la senzillesa i quotidianitat d’un museu. Tot i així, parlaria més aviat de la possibilitat de senzillesa del museu, perquè actualment hi ha una maquinària ideològica, econòmica, i cultural que posa molt d’esforç en evitar que siguin espais quotidians. L’armadura que s’ha construït al voltant de les institucions museístiques forma part d’un llegat ideològic capitalista, conservador i autoritari, entre altres coses. En nom de la “conservació” del patrimoni o de l’objecte artístic, s’ha creat més i més distància entre l’experiència de compartir coneixement i vivències properes, connectades amb el nostre entorn immediat. El projecte “Investigació entorn de la taula” busca reivindicar la necessitat de “quotidianitzar” el museu i, alhora, donar valor al que és quotidià. És un procés a vegades difícil per la por a la banalització de la cultura i de l’art. Però apropar no significa banalitzar! Aquest binomi també té unes arrels ideològiques que perpetuen la idea que allò proper, senzill i del dia a dia és banal. A més d’aquesta voluntat de reivindicar el museu com a organització possible, quotidiana i propera, una transició cap a una societat més equitativa necessita explorar molts més processos que requereixin pocs recursos energètics, humans i materials. M’agrada sempre subratllar la importància del DIY i del low-fi en aquest sentit més polític. I si partim de la visió de la col·lapsologia, que un col·lapse socioecològic és ara mateix inevitable, el low-fi serà molt necessari. Citant l’autor Ivan Illich: “La revolució només vindrà en bicicleta”.

- La reflexió sobre museus i la relació de l’art amb l’audiència és un tema recurrent en el teu treball artístic. Pel que fa a la taula, relaciones aquest element amb l’anomenada ‘estètica relacional’. Quina és la teva relació amb aquest llegat?

Si parlem de pràctiques de procés i de treballs participatius o comunitaris, o de mediació, és evident que per a mi són claus per entendre el gir que els espais culturals han de continuar fent. És cert, però, que la utilització d’aquests formats o processos per fer “social washing” és una tragèdia que persisteix. Els processos inclusius, de llarg termini, de reflexió i d’experiències conjuntes són necessaris per abordar problemàtiques difícils i complexes. Això no vol dir, però, que la responsabilitat recaigui només en l’artista ni en l’”obra artística”, com s’ha fet moltes vegades. Aquests processos han de ser mediats des de diverses posicions, tant dins com fora de les institucions culturals. Projectes de procés i de treball col·lectiu han de ser sostinguts per polítiques culturals, pel sistema de finançament de la cultura, pels models de comunicació de les organitzacions culturals, per com s’estructura la producció i l’equip al voltant dels processos artístics, i, finalment, pels artistes. Ho dic perquè m’he trobat en molts casos en què, per molt que com a artista s’iniciï un procés de treball col·lectiu i d’obra en format d’esdeveniment, si la institució no té la voluntat que aquell procés s’allargui en el temps, aquell projecte i esforç poden acabar tenint poc impacte real. Per tant, en aquest sentit, el format de l’obra no garanteix cap mena de més o menys efectivitat en termes d’impacte social o polític, sinó que això depèn més aviat del contingut, i sobretot del context i de tota l’estructura que l’envolta. Diria, per tant, que el fenomen de l’estètica relacional descrit per Bourriaud en el seu llibre és una mena de caricatura del que realment es pot aspirar en aquesta direcció. És molt més interessant en aquest marc observar com aquestes problemàtiques han estat abordades des de les institucions, des de l’activisme o des d’altres organitzacions que no són del món de l’art. Per a mi, l’error és donar tanta importància a l’obra i a l’artista. Però tota aquesta riquesa que poden tenir els processos de treball col·lectius, de reflexions i d’experiències compartides ja es treballa moltíssim en altres entorns: entorns més quotidians, familiars, socials o d’activisme. Per tant, repeteixo el que deia en la pregunta anterior: es tracta de donar més valor i potser suport a aquests processos “quotidians” i, d’alguna manera, “quotidianitzar” més les institucions artístiques.

- L’humor és un element característic del teu treball. Té a veure amb la relació que vols mantenir amb l’audiència, així com amb els teus objectes d’estudi?

Continuo treballant amb l’humor, tot i que en els últims anys hi tinc una relació més complexa. L’humor té la capacitat de generar proximitat però, alhora, distància. M’atreveixo a dir que l’humor en la cultura popular, de la qual més m’he nodrit, té una herència patriarcal molt forta. L’humor com a manera de treure “importància” a temes o de no posicionar-se és molt perillós. També veiem com la cultura popular americana dels anys 90 (la qual m’ha influenciat moltíssim), com The Simpsons, South Park, Saturday Night Live o la música de Ween, és un clar exemple de com es permetia perpetuar valors sexistes, xenòfobs, transfòbics i tòxics. Per altra banda, en alguns casos l’humor permet treballar temes complexos i difícils integrant les seves contradiccions. Charlie Brown, per exemple, explorava la part innocent però també tràgica de la infància. Charlie Brown era una eina per vehicular els debats interns que tenia el seu autor, Shultz, sobre la seva masculinitat i els seus valors contradictoris sobre l’èxit, l’acceptació social i les relacions amoroses. Un altre exemple molt més polític i social seria Mafalda. Podem trobar molts exemples de com l’humor ha servit per exposar idees importants al llarg de la història de la cultura i de l’activisme. En el meu cas, però, no sé si l’humor és una eina important per relacionar-se amb el públic o més aviat per navegar la complexitat d’un debat. Personalment, m’ajuda a explorar les meves emocions i reflexions, sovint poc clares. Per mi, l’humor em permet treballar la tendresa, l’estranyesa, la ràbia, l’amor i la por tot en un. Podria ser també que sigui una manera de no posicionar-me, però de moment és la manera que he trobat per endinsar-me en processos de reflexió que, si no, em costarien més. I de moment sembla que l’audiència també ho entén i li permet connectar amb aquest panorama d’emocions.

(engl)

One aspect of your research on the table that I’d be interested in discussing is the effect you’re aiming to achieve when this work is displayed in a museum. On the one hand, with the table, you highlight an aspect of museum displays that often goes unnoticed. However, when you reduce all the sophistication of display design to the table component and emphasize its condition as a common denominator, it also seems like you’re trying to reveal the museum as a much more domestic and everyday artifact than it initially appears to be.

Exactly. Talking about the simplicity or everyday nature of the table is a way of talking about the simplicity and everyday nature of a museum. However, I would rather speak of the possibility of simplicity in the museum, because right now there is an ideological, economic, and cultural machinery that puts a lot of effort into ensuring that these are not everyday spaces. The armor that has been built around museum institutions is part of an ideological legacy that is capitalist, conservative, and authoritarian, among other things. In the name of “conservation” of heritage or the artistic object, more and more distance has been created between the experience of sharing knowledge and close, connected experiences with our immediate environment. The project “Research on the Table” seeks to continue advocating for the need to “everydayize” the museum while also valuing what is everyday. It is a sometimes difficult process due to the fear of trivializing culture and art. But bringing things closer does not mean trivializing them! This binary also has ideological roots that perpetuate the idea that what is close, simple, and part of daily life is trivial. Beyond this desire to claim the museum as a possible, everyday, and approachable organization, a transition to a more equitable society needs to explore processes that require fewer energy, human, and material resources. I always like to emphasize the importance of DIY and low-fi in this more political sense. And if we consider the perspective of collapse studies, where a socioecological collapse is currently inevitable, low-fi will be very necessary. As the author Ivan Illich said: “The revolution will only come by bicycle.”

Reflecting on museums and the relationship between art and the audience is a recurring theme in your artistic work. Regarding the table, you associate this element with so-called ‘relational aesthetics.’ What is your relationship with this legacy?

When it comes to process-based practices, participatory or community work, or mediation, it’s clear that for me, these are key to understanding the shift that cultural spaces need to continue making. However, it’s also true that the use of these formats or processes for “social washing” is a tragedy that persists. Inclusive, long-term processes of reflection and shared experiences are necessary to address difficult and complex issues. This doesn’t mean, though, that the responsibility lies solely with the artist or the “artistic work,” as has often been the case. These processes must be mediated from various positions, both within and outside cultural institutions. Process projects and collective work need to be supported by cultural policies, the cultural funding system, communication models of cultural organizations, how production is structured, and the team around artistic processes, and finally by the artists. I say this because I have encountered many situations where, even though as an artist I initiated a collective work process or an event-based piece, if the institution doesn’t have the will for that process to be extended over time, that project and effort may end up having little real impact. Therefore, in this sense, the format of the work doesn’t guarantee more or less effectiveness in terms of social or political impact; rather, it depends on the content and especially on the context and the entire structure surrounding it. I would say, therefore, that the phenomenon of relational aesthetics described by Bourriaud in his book is somewhat of a caricature of what can actually be aspired to in this direction. It’s much more interesting in this framework to observe how these issues have been addressed by institutions, activism, or other organizations outside the art world. For me, the mistake is placing so much importance on the artwork and the artist. But all the richness that can be found in collective work processes, shared reflections, and experiences is already being widely explored, but in other environments—more everyday, familial, social, or activist settings. So, to reiterate what I said in the previous question, it’s about giving more value and perhaps support to these “everyday” processes and, in a way, “everydayizing” art institutions more.

Humor is a characteristic element of your work. Does it relate to the relationship you want to maintain with the audience, as well as with your subjects of study?

I continue to work with humor, although in recent years my relationship with it has become more complex. Humor has the capacity to create both proximity and distance. I would even say that humor in popular culture, from which I have drawn a lot, has a strong patriarchal heritage. Humor as a way of downplaying issues or avoiding taking a stance is very dangerous. We can also see how 1990s American popular culture (which has greatly influenced me), such as The Simpsons, South Park, Saturday Night Live, or the music of Ween, is a clear example of how it allowed the perpetuation of sexist, xenophobic, transphobic, and toxic values. On the other hand, in some cases, humor allows us to address complex and difficult topics while integrating their contradictions. Charlie Brown, for example, explored the innocent but also tragic side of childhood. Charlie Brown was a tool for his creator, Shultz, to express his internal debates about his masculinity and his contradictory values regarding success, social acceptance, and romantic relationships. Another much more political and social example would be Mafalda. There are many examples of how humor has served to expose important ideas throughout the history of culture and activism. In my case, however, I’m not sure if humor is an important tool for relating to the audience or more of a way to navigate the complexity of a debate. Personally, it helps me explore my often unclear emotions and reflections. For me, humor allows me to work on tenderness, strangeness, anger, love, and fear all at once. It could also be a way of not taking a definitive stance, but for now, it’s the way I’ve found to delve into reflective processes that would otherwise be more challenging for me. And for now, it seems that the audience also understands this and is able to connect with this panorama of emotions.